Restoring Habitat, One Yard at a Time

It was a beautiful spring day in 1995. I had recently retired and was enjoying my volunteer work at Habitat for Humanity. On this particular day, I was relaxing on my backyard patio, gazing at the expanse of lawn and surrounding shrubbery, all meticulously manicured except for an old, dead almond tree which had fallen over in a storm the previous winter and I had not gotten around to removing. I began to think: I’m helping to build homes for people, but what about habitat for wildlife? If I was a bird or butterfly, would I want to even visit this yard, much less live here? Is there food for birds and other critters? Except for some old walnut trees that provided nuts for the squirrels, the answer was “no”. Is there water for drinking and bathing? No. Is there shelter to protect them from the weather and from predators? Very little. Are there places for them to raise their young? Again, the answer was: very little. And I realized something else: our backyard was very boring!

I began to visualize what a habitat for wildlife would look like in our yard. It had separate “rooms” that were not visible until you got there on paths of natural material that led from room to room. It had dense foliage: tall trees, tall and short shrubs, ground cover, rock piles and brush piles that provided shelter and places for critters to raise their young. It had plants that provided food in the form of seeds, nuts, berries and nectar. And it had a variety of water sources, some running and some still.

I drew up a plan based on my vision and, over the next couple years, I had transformed our yard. Most of the lawn was gone (it had very little value for wildlife and consumed an enormous amount of energy and resources caring for it), replaced by all of the things I had visualized on that spring day. I added a dry stream bed, which not only added interest and sheltering rocks, but also collected rainwater and solved a drainage problem. The bug-ridden, fallen almond tree remained, providing food for woodpeckers and some other, larger dead trunks were left on some trees that provided cavities for nesting sites.

Flushed with a feeling of success, I turned my attention to our front yard. There was a very large patch of Algerian ivy as well as more lawn that I replaced with wildlife attracting shrubs, trees, perennials, and vines. My wife’s beloved rose bushes remained, but no longer required pesticides because the birds that flock to our garden eat the aphids. I also began using plants that are native to our region because they require very little water once established and no food, in contrast to non-natives. In addition, native plants are more attractive to native wildlife (obviously!).

Our garden now looks very different than most of our neighbors’ gardens. It no longer looks meticulous. It requires much less maintenance and much less water and other resources. Most of the leaves that fall remain on the ground where they serve as mulch and hide bugs for insect-eating birds. Our old asphalt driveway has been replaced by the same material I used for the garden paths,- decomposed granite. And, best of all, our more natural garden has attracted 51 species of birds (to date), butterflies, lizards, beneficial insects, the occasional possum and raccoon, in addition to the squirrels.

Fast forward to 2015. I have been volunteering with Wildlife Care of SoCal for about 18 years now; I have had my yard certified by the National Wildlife Federation as a “Backyard Wildlife Habitat” and am volunteering as a wildlife habitat steward for that organization and as the Audubon-at-Home Chair for the San Fernando Valley Audubon Society, helping others transform their yards into spaces that are attractive to both humans AND wildlife.

As I wander through our garden now, I think that it is not only a habitat for wildlife, but that it, too, is a habitat for humanity, for what would my life be like if earth’s wild and beautiful creatures were not a part of it?

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Feed me…..feed me

This month’s article and next month’s will be about the basic elements needed for creating a wildlife habitat in your yard. Wildlife needs just about the same things that we humans need for survival: food, water, shelter and places to raise young. Of course we humans have some additional requirements….like our morning latte…First, then, is food.

Plants are the best source of food for (non-predatory) animals. They provide seeds, nuts, berries, nectar, foliage, and attract insects which are also part of the diet of many critters. Since critters may forage for food in specific locations (on the ground, in low shrubs and flowers, in tall brush and trees), it’s wise to have food sources in all those locales. By providing a diverse plant community in your garden, you are most likely to achieve a balanced eco-system that will sustain itself. Plant sources can be supplemented with feeders of various types. Bird feeders should be cleaned regularly, placed where predators can be observed approaching and close to protective shelter should escape be needed.

Critters need water for drinking and bathing. Water sources can vary between the very simple and the very complex, depending on your preferences, location and budget. A shallow dish or hollow rock sitting on a stump or hung in a tree is easily provided. Bird baths and water fountains require a bit more effort. Birds will come to still water, but are especially drawn to dripping or moving water. Birds need only about ¾” deep water, so if your water container is deep, adding some rocks will provide a standing surface for short-legged birds. Water will need to be changed at intervals so that it is clean. Chlorox can be used to eliminate algae build up. More elaborate water features include streams and ponds, either natural (if you’re lucky!) or man-made. These, of course, require more expense and care. With any source of water, care must be taken to avoid providing a breeding ground for mosquitos, the carriers of West Nile Virus and other diseases. Mosquitos can’t breed in moving water. With still water during mosquito season, changing it often, adding fish, or mosquito dunks (a larvicide which does not harm other animals, available at garden nurseries) will eliminate the problem.

So, to borrow from a baseball phrase – feed and water them and they will come!

Alan Pollack, M.D.

“Home, home on the range…”

Like humans, wildlife needs shelter from the elements, protection from predators, and places to raise their young. Recall your last visit to a wilderness area, and what you likely saw were tall, mature trees, smaller trees and tall shrubs, dense foliage and some smaller plants providing some ground cover. Additionally, you may have seen rock piles, brush piles, leaf litter and dead trees, either standing or fallen. All of these provide homes and/or temporary shelters for wild critters, whether it is the great blue heron nesting at the top of a large tree or the creepy-crawly insect under the leaf litter. By planning your garden with these elements, you are imitating Mother Nature’s design, which is to provide shelter at all elevations. Notice that Mother Nature is not a neat and tidy housekeeper, so if you have a meticulous, manicured yard, it is a wildlife unfriendly yard. (Please note: if you live in a fire zone, you need to ignore much of what I am recommending here.)

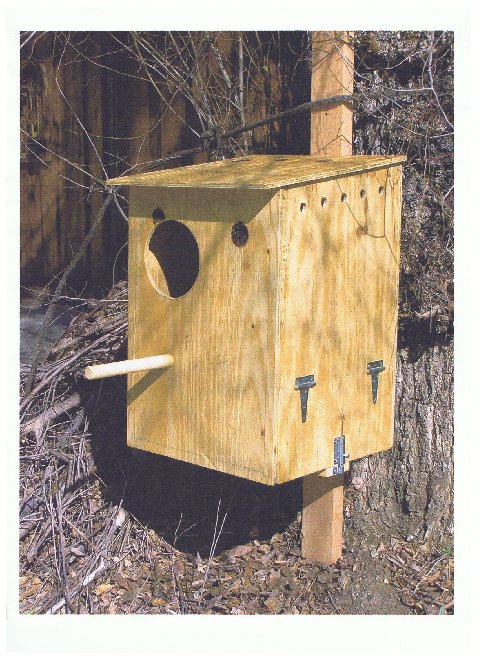

Notice the inclusion of dead trees. Those who study such things have observed that dead trees are as important to a balanced eco-system as live trees. As they age and die, they attract insects which feed on them and, in turn, these insects are food for other species. In the process of dying, cavities may appear in the tree, sometimes aided in formation by a hungry woodpecker. These cavities then become shelters and/or nesting places for various bird or mammal species. Finally, when the tree falls and rots, its nutrients are returned to the soil for recycling. So, rather than removing that dead or dying tree in your yard, have a tree trimmer remove only the large limbs that may pose a danger to someone walking close to the tree and let the remainder stay in your garden. One can also provide birdhouses to supplement the housing for cavity nesting birds.

Some species have needs not mentioned above. Frogs and amphibians, of course, need wetlands or a water garden. And if you want butterflies to live in your garden and not just visit, you will need to plant those species of plants that are specifically a host plant for that butterfly. Each butterfly species has either one or just a few host plants on which it will lay its eggs and the larvae (caterpillars) will feed.

The kind of gardening described above is called “naturalistic”—it is an effort to restore natural habitat. I find that my naturalistic garden requires far less work to maintain than my neighbors’ meticulous yards. Leaf and needle litter remains where it falls (providing nature‘s mulch), except if it hides a path. Plants are allowed to grow to their natural size and shape and are only pruned if they obstruct in some way or annually if it is required for growth. By using native plants, feeding is eliminated. Mulching keeps weeds at bay (no herbicides are needed). Some insect-caused leaf damage is tolerated and the good bugs and insect-eating birds visiting in the garden keep the bad bugs under control (no pesticides are needed).

This kind of gardening does, however, have its risks. These are mostly in the form of complaints from those who don’t understand why such a garden looks so different than all the others in the neighborhood—they confuse naturalistic with neglect. Complaints have been known to reach the courts in some cases. There are ways to mitigate such risks. This is what I did: I invited all the neighbors to an open garden party/tour, explaining what naturalistic gardening is all about. By creating paths, adding places to sit, and garden art, the garden appears designed rather than neglected. By having the yard certified by the National Wildlife Federation as an official wildlife habitat site and posting certificate signs in the garden where passerby can see them, they are informed and, perhaps even inspired to make some landscaping changes of their own.

How about your yard? Neat as a pin or inviting to wildlife?

Alan Pollack, M.D.

“Have some poison, my dear….”

Just suppose you gave a party for some dear friends and without being aware of it, many of the dishes you served up were poisoned! Not a pleasant thought, but that is exactly the scenario that takes place when you reach for the rodentacide, insecticide or herbicide to get rid of those pesky moles, insects, or weeds in your garden. Your garden is an invitation to our wildlife friends and they eat what is served, including the just poisoned rodent, insect or weed. And let’s not forget that as these poisons are being applied and leach into the soil and water table, humans are also being exposed and slowly poisoned. So, what are the alternatives? There are many! Let’s consider one problem at a time.

PESTS, such as rats, moles, mice, etc. Eliminate food sources (such as fallen fruit, or dog and cat food placed outdoors) and shelter (such as large patches of Algerian ivy) . Build or buy nesting boxes to attract barn owls (one family of barn owls will eat 1000 or more rodents/year). If you must, traps that kill quickly and humanely.

INSECTS: To begin with, learn to distinguish harmful from beneficial insects, such as praying mantids, assassin bugs, green lacewings, lady beetles, and hover flies. Biologic control is an effort to keep insects controlled (not eliminated) and begins with purchasing plants that are resistant to insect attack and/or are attractive to beneficial insects. Most often these are plants that are native to your area. Keep plants healthy by first, choosing plants likely to grow well in your garden spot (and again, natives are a good choice) and by giving them the proper water, food (if needed) and maintenance. Watch for early signs of disease or infestation. If either is observed, mechanical controls include removing the diseased portion of the plant or, the whole plant, if necessary; a strong spray from your water hose can remove clinging insects; a gentle spray of water in the morning will get rid of powdery mildew (whereas at night, it will encourage mildew). If chemical controls are necessary (hopefully, the last resort), using the least toxic is best for our environment. Many common household products can be effective and are less harmful than the chemicals sold in garden stores. For example, a mixture of baking soda and liquid soap will treat both blackspot fungus and powdery mildew. An insecticidal soap solution can be purchased at garden stores. In time, when the good bugs establish themselves, these measures will be unnecessary.

HERBICIDES Most of the herbicide use in the U.S. is applied to lawns. Since a lawn has very little value for wildlife and also consumes an enormous amount of water, fertilizer, and care (read $$$$$) in addition to herbicide, reducing the size of (or totally eliminating!) your lawn would make a big dent in herbicide use. And since Mother Nature abhors bare soil the way she abhors a vacuum, keeping a layer of mulch on all bare soil areas will inhibit weed growth (as well as conserve soil moisture and improve soil structure). When weeds appear, pulling them out works well (best done before they go to seed) and is good exercise! Weeds in cracked concrete or asphalt can be killed with a propane torch or a strong vinegar solution.

Learn more about non-toxic, environmentally-friendly, sustainable gardening practices at www.finegardening.com (click on pests and diseases).

There, now, aren’t you less worried about throwing your next “garden party”?

Alan Pollack, M.D.

A water-wise, wildlife garden…part 1

We living here in Southern California are lucky to be in a Mediterranean climate where a huge variety of plant species can grow. However, we are not so blessed when it comes to rainfall. Here in the L.A. area, in the last 25 years, we have received our 14” average rainfall only 8 times. This proneness to drought could extend for years and some experts are speculating, for decades into the future. It is therefore imperative to implement water conserving measures in our gardens. In this article and in next month’s, I offer some suggestions.

The first and perhaps the most efficacious for saving water, is to reduce or eliminate lawn. It is estimated that there are 20-30 million acres of lawn in the U.S.. The expansive, manicured lawn tradition found it’s way to this country from soggy olde England, where it evolved as a status symbol: the more acres of sod lawn you had, the richer you were. In most cities in the U.S., lawns consume between 30-60% of municipal water supplies and, in some areas (like the San Fernando Valley where I live) that figure is probably closer to 80%. And of what value is lawn for wildlife? Almost none.

The lawn story gets worse: in addition to water gluttony, large swaths of lawn are often doused with millions of pounds of synthetic pesticides and herbicides which negatively effect the eco-system in our soil, as well as poisoning any critter that happens to feed on the poisoned lawn pest (and so on up the food chain). Add to that the millions of pounds of chemical fertilizers applied to lawns and consider that all of these chemicals will percolate into our groundwater or run-off ( because many homeowners over-water their lawns) into our streets, sewers, streams, rivers, and ultimately the ocean where they do their toxic damage. (There are now over 400 dead zones in the planet’s oceans where nothing grows because of the pollutants we dump in them.) And let’s not forget the CO2 that is pumped into the atmosphere from all those gasoline powered lawn mowers and leaf blowers. And last, but not least, there are the health problems that all these products potentially cause, especially in children and in the workers who use them regularly.

Alternatives to lawn: if the lawn has been used for children to play on, consider a low growing, low water using, low maintenance native ground cover or an unplanted area of decomposed granite. If the lawn has been simply decorative, consider replacing it with a meadow of native grasses and perennials, or beds for native plants connected by paths of decomposed granite, or a rock garden, or a succulent garden. Any of these choices will not only conserve water, but also save you time, energy and money. And let’s not forget that in the process, you will also be providing a welcoming habitat for our wild friends.

A water-wise, wildlife garden – part 2

In addition to reducing or eliminating lawns (which I addressed in my last article), there are many other measures we can take to conserve precious water in our gardens.

Capturing rainwater and overhead sprinkler water:

Replace non-porous surfaces (concrete, asphalt, brick, etc) with porous ones (decomposed granite, gravel, etc). Instead of water running off into the street and sewer system (with it‘s toxic brew of chemicals if you haven‘t eliminated those) , it will percolate into your garden soil and into the water table. An added bonus: by removing materials that are heat trapping, you will lower the temperature around your home.

Create swales and dry stream beds which will act as collectors.

Place rain barrels under downspouts. (Because it’s acidic, when used for potted plants, you might wish to dilute/neutrapize with our alkaline tap water.)

Using low-water-using plants: preferably native plants. (more on this subject in future articles).

Using drip, soaker hose, and hand irrigation:

These methods put water where it’s needed, into the soil directly in contrast to sprinkler systems where much water is lost to evaporation and runoff. Where overhead sprinklers are used, they should be scheduled for the early morning hours, e.g., 3-6 a.m., and only for a long enough duration to irrigate without causing runoff. And if you want to drive me really crazy, water your lawn during or right after a heavy rain. Sprinkler control systems can and should be turned off during the rainy season…if we ever get one of those again.

I’ve come to regret putting in a drip system in a portion of my garden because some of the critters that are attracted enjoy chewing on the drip lines! I’ve decided sensibly used overhead watering is less troublesome and natives prefer it too.

Mulching

A mulch is any material placed on the surface of the soil which helps to retain it’s moisture. In addition, a mulch suppresses weed growth (Mother Nature abhors bare soil the way she abhors a vacuum,- leave it bare and something will grow…usually weeds), provides habitat for creepy, crawly things, and, if it’s an organic material, it’s slow decomposition improves soil structure. The leaves and pine needles that fall from our trees are nature’s mulch and can be left where they fall in your planting beds. Other organic mulches include grass clippings, bark chips, wood chips, straw and the compost that can be made from collected organic materials. The city of Los Angeles and some surrounding cities provide free mulch for the taking (check with the City website, Dept of Sanitation in L.A., to get locations). Inorganic mulches are things like rock chips and gravel. A very low-growing ground cover can serve a similar purpose, though obviously requires some watering.

Use of gray water: where it is permitted. Gray water is the water that comes from your kitchen, laundry, bathtub and shower (i.e., all water sources other than the toilet). It takes some special plumbing, but it works.

So, which will you be? A water-wise gardener or a water-wasting one?

Alan Pollack, M.D.

“Boy, it stinks here, Dad”

Those were the memorable words of my son as we sat down on a bench in my garden near my compost pile. Then he looked at me, saw my smile, and then he smiled too and said “….and you probably love it, don’t you?”. Yes, Adam, I really do. It is the smell of fresh earth pulsing with life.

It has been said that humans are the only animal on the planet that takes out of the earth more than it puts back (in usable form). Every other species puts useful stuff back into the earth where it is recycled into new life and some species do more than their share, e.g., the ants. Even death, which for most species means the elements of life being reassembled into new life, means being locked in an impermeable box or urn for humans,- our life stuff unavailable (at least for a long time) to create new life. Composting in your garden is one, small way to aid Mother Nature in maintaining the cycle of life….nature’s balancing act.

Building and maintaining a compost pile requires very little effort. One doesn’t need any fancy boxes or bins to create compost, though those are available to build or buy. All one needs to do is create a large pile of vegetable (I.e., no animal flesh) matter and keep it moist (not soaking wet): brown stuff (dead leaves, straw, horse manure) and green stuff (leaves, grass clippings, weeds, kitchen scraps) in alternating layers.

You would be wise to avoid adding weeds that have gone to seed, as some of these can withstand composting. It needs to reach a certain size before it begins to “cook”. Smaller amounts of vegetable matter will decompose too, just at a slower rate. Building it in a shady spot helps keep it moist and turning it every so often helps aerate the pile and will speed the process. Decomposition takes a few months and generates heat (you will see steam arising from the pile as it “cooks”). In the absence of animal flesh, no flies are attracted to a composting pile. When fully “cooked”, the material is no longer recognizable as the material that you put in, but as a dark, crumbly material teeming with life that smells like Mother Earth herself! Use it as a mulch on the surface or dig it into soil that you want to enrich or improve (but don‘t do the latter for native plants! They are accustomed to our native soil). In fact, if you would like to make a flower bed or vegetable garden in an area that has poor soil for growing things, build a compost pile on that spot. If it’s a grass area, cover it with cardboard or several layers of newspaper first. These will also decompose and once most of the compost has been removed, the soil beneath will be vastly improved and ready for planting.

If, for whatever reason, you are unable or don’t wish to keep a compost pile, make sure you (or your gardener) put(s) all your yard trimmings in the city’s green barrels (only) and the city will compost it for you and make it available, for free, at several locations in LA. It’s not the rich stuff one can make at home, but it has it’s uses as a mulch.

And there’s one more use for a compost pile that I‘ve discovered: dogs LOVE to play “hide the ball” in it! And that helps to keep it mixed!

Alan Pollack, M.D.

HEALTHY SOIL FOR A HEALTHY WILDLIFE GARDEN

A healthy, wildlife garden, like any other garden, is built on healthy soil. This article focuses on ways to keep it so.

AVOID PESTICIDES: In an earlier article (“Have some poison, my dear”) I wrote about how these toxic chemicals travel up the wildlife food chain, killing as it goes. At the bottom of the food chain are the small and microorganisms that inhabit the soil and are a vital part of it’s ecosystem. In a balanced garden, there are pests and there are predators that feed on the pests and keep them in check. (Incidentally, tilling the soil is another way of disrupting the soil’s ecosystem. Rather than tilling to get rid of weeds, spread mulch to inhibit weed growth. More on mulching below.)

AVOID CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS: Plants need food only during their growing season and then in a slow, measured fashion. Chemical fertilizers force feed a plant and stimulate rapid, unnatural growth. Kinda like cocaine for plants. Research has shown that plants are healthier and last longer when provided with organic fertilizers such as manures of various kinds and compost. As these natural, organic materials decompose, in addition to plants being fed, the soil structure is improved. If you want to avoid feeding altogether, put native plants in your garden. In most cases, fertilization is not only unnecessary, but will actually kill the native plant.

MULCHING: I wrote about mulching in reference to being water wise,—keeping the soil cool and retaining moisture. If the mulch is an organic material, as it slowly decomposes it’s nutrients return to the soil, enriching it. Organic mulches of various kinds can be purchased or obtained free from your city’s recycling program. By letting the leaves and pine needles and other falling litter remain in planted areas, Mother Nature is providing us with mulch delivered free of charge to your garden beds.

PREVENTING EROSION: Erosion is often a problem for those living on sloping ground or hillsides. The usual strategies include terracing, retaining walls or berms, drainage channels, and keeping the hillside or slope planted. Many native plants are useful for this purpose as they have deep root systems and some do an especially good job of holding soil in place.

Successful gardening begins with attention to our garden’s soil. Be good to it and it will nurture your garden’s plants,– home to and food for the wildlife you hope to care for.

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Are you living with a killer?

The domestic cat, like its larger cousins in the wild, are territorial creatures. The size of its territory is a function of its food supply: the more food that is available, the smaller its territory needs to be. Where food is available on a regular basis and at the same place, as in a household, a cat’s territory is likely to be small areas within the house itself. Domestic cats, then, do not need to be wandering loose outdoors and there are very good reasons to keep them indoors.

Roaming cats are food for larger predators and they are also vulnerable to contagious diseases and being killed by cars. They are also the greatest threat to our bird population, killing HUNDREDS OF MILLIONS of birds each year. Even well fed cats will do this, as the instinct to hunt is distinct (in the cat’s brain) from the need to eat. They do it just for fun. The feral cat population can be kept in check if there are larger predators in the area, but if that is not the case and/or if well meaning people help to sustain the feral cat population, that worsens the problem for our birds.

We can protect our feline friends and our birds by not letting kitty wander outdoors. A fresh air experience can be provided, if necessary, by an enclosure outdoors, a screened porch or window, or training kitty to walk on a leash. And if you don’t have coyotes in your neighborhood, if you let the cat out at night it will hunt rats and mice. Kitty and our birds will thank you!

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Our precious pollinators

Imagine a world with no flowers, no fruit, not even a cup of coffee. That’s the world we would live in were it not for the daily efforts of birds, bats, butterflies, moths, bees, beetles and other pollinators. Estimates differ on how much of our food supply depends on pollinators, but it probably ranges between 30% and 60%.

Studies are now showing that there is an alarming loss of pollinators world wide. One likely reason is that as acreage is cleared of native plant life to make way for crops and pasture, the native pollinators also disappear.

Another explanation is likely the widespread use of insecticides, which do not discriminate between harmful insects and beneficial ones and those poisoned insect pollinators are ingested by other pollinators, such as birds and bats, which are then killed off as well. For generations, European honey bees have been imported to this country to supplement indigenous pollinators in pollinating our food crops, but these also are now threatened. Honey bee hives have been decimated worldwide in recent years, first by a parasitic mite and, more recently, by a phenomenon termed Colony Collapse Disorder. Scientists may recently have determined the cause of CCD, but a cure is still not at hand.

So, what can we homeowners do to make life easier for our precious pollinators? We can do what I have been writing about in this series of articles: we can create gardens that are wildlife friendly by using native plants; by including flowering and nectar producing plants; by learning to accept the bug life in our gardens along with the birds and butterflies; by avoiding the use of pesticides; by educating our children about beneficial insects in the garden; by calling a bee-keeper, not an exterminator if you find an unwanted hive in your garden; and by restoring habitat. Protecting our pollinators means food on the table….literally.

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Want wildlife? Go native!

California native plants are those which are indigenous to our state,- they were here before the European settlers arrived. There are over 6000 species of California natives and another 6000 plus cultivars developed from those. There has been a rapid decline of our native flora as a result of massive development and as homeowners and landscapers import plant material from distant regions. The record drought in the mid- to late 1970’s sparked interest in restoring and conserving our native flora and our current drought (now in it’s fifth year) should add further impetus to this trend if one is at all environmentally conscious and concerned.

In addition to the effort to conserve our natural flora, there are other good reasons to go native. Native plants are adapted to our climate because most have deep root systems. Most can survive drought, frost, wind and fires (if they are not too frequent). Once established, many will survive on little or no irrigation. They are adapted to our generally poor soil. Amending the soil and fertilizing is not just unnecessary,- it will often kill the plant. Allowed to grow to their natural size and shape, they require less pruning, which may be needed only for aesthetic or health reasons or to rejuvenate the plant. And, finally, native plants attract and support our native wildlife, including pollinators and insect predators, eliminating the need for environmentally harmful pesticides.

And then there are good reasons to avoid and, in some cases, eliminate non-native (aka, exotic) plants from our gardens: Removed from their natural habitats (where there are typically built-in controls to their growth) and planted in a strange, new habitat (where such controls often do not exist), non-natives may grow rampantly, displacing our native flora. Many are very thirsty and some pose extreme fire hazard. Finally, they may offer little support to our native wildlife.

To learn more about native plants and how to use them in your garden, check out these websites: www.cnps.org (California Native Plant Society, where you can find a list of plants native to your zip code) and www.theodorepayne.org (many plant lists in their education page). Some excellent books are “California Native Plants for the Garden”, by Bornstein et al; “The Care and Maintenance of Southern California Native Plant Gardens” by O’Brien et al; “The California Wildlife Habitat Garden”, by Nancy Bauer.

As to purchasing natives, most of our local (San Fernando Valley) nurseries carry few, if any. But the more people who request natives at their local nursery, the more likely the nursery is to start carrying them. Theodore Payne in Sunland is a retail native plant nursery and Matilija, though located in Moorpark and a bit of a drive, is a wholesale native plant nursery open to the public at certain times. Go to their website (www.matilijanursery.com) to find out how to get there and the hours it’s open for the walk in trade.

If you go native, our wildlife friends will thank you by coming to visit more often!

Alan Pollack, M.D.

SELECTING NATIVES FOR YOUR WILDLIFE GARDEN

A good way to start the selection process is to know what plant community you reside in and obtain a list of plants that make up that community. You can do that by googling “plant communities by zip code”. That will take you to the website laspilitas.com where you enter your zip code and at the bottom of the page that appears, click on list of plants. Click on the listing and up comes a good photo and a paragraph or two describing the plant and all of its needs. One needn’t restrict one’s choices to just that one community, as some plants from other communities might also do well. For example, though most of Los Angeles is Coastal Sage Scrub, plants from Chaparral, Oak Woodland, and Desert habitats can do well here.

Know what kind of soil is in your garden. Much of the San Fernando Valley has clay soil, but there may be pockets of sandy soil or loam, or a combination of any of the above. An easy test: grab a fist full of moistened soil and make a ball. If you can’t make a ball at all, there is a lot of sand. If you make a ball and poke your finger into it and it crumbles readily, the soil is loamy. If the ball stays intact with the hole you poked, it’s mostly clay. Knowing the soil type tells you something about the drainage, with sand being the fastest, clay the slowest, and loam in the middle. One can also dig a hole, fill it with water and see how long it takes for the water to absorb. Sand will not retain water at all and some clay will retain water for hours. Absorption within 30 minutes is considered good drainage.

Observe the amount of sunlight each part of your garden receives: plants needing “full sun” require sun all or most of the day; plants needing “shade” require little or no sun; and those needing “half-shade” require sun for about half a day.

If you are adding a plant to an area that is already planted, consider its neighbors. I.e., what plants are growing nearby and are the needs of the new plant the same as it’s neighbor’s? For example, an established oak tree does not like much water, so one wouldn’t put thirsty shrubs or perennials under an oak. Then, there are some trees, like the walnut, that are allelopathic: the roots secrete a substance that inhibits the growth of many plants in the root zone, while some other plants are able to survive.

Help is available. Native plant nurseries have websites: laspilitas.com; matilijanursery.com; Theodorepayne.org…to name a few. Lacnps.org is the Los Angeles California Native Plant Society’s website. There are people at the nurseries who can give advice. And, finally, there are books on the subject. A favorite of mine (considered the “bible” of native plants) is “California Native Plants for the Garden”, by Bornstein,Fross, and O’Brien.

Since it is always unpredictable if a given species of plant is going to do well in a particular location in your particular garden, it is monetarily wise to plant only 2 or 3 of any species at first to see how it does.

Alan Pollack, M.D.

PLANTING, CARE AND MAINTENANCE OF YOUR NATIVE, WILDLIFE GARDEN

Although one can plant at any time, the best time to plant natives (and non-natives, for that matter) is in the late fall, just before the rainy season. The cooler weather and winter rains minimizes the amount of watering necessary to help plants get established before the dry, hot summer.

Planting is pretty simple: dig a hole twice the width and twice the depth of the pot the plant is in. If the soil is dry, fill it with water one or more times before planting. Refill the hole with the same soil that was dug out so that the surface of the root ball is slightly higher than the surrounding soil. Remove the plant from the pot with as little disturbance to the root ball as possible. Obviously, if it is rootbound, one needs to scratch the surface of the rootball to free up the roots a little. With the plant placed slightly higher than surrounding soil, continue to refill with the original soil. With rare exception, DO NOT ADD ANY AMENDMENTS OR FERTILIZER. Use a chopstick or other poker to make sure air pockets are filled with soil. With left over soil, create a basin wall at the dripline of the plant. Add a layer of mulch around the plant, but not touching the trunk/stem crown. Give it some more water to settle the soil and you’re done.

Until they are established (usually 2-3 years), all natives require watering. If you’ve planted at the beginning of the rainy season, Mother Nature will take care of much of that. If there isn’t much rain or you’ve planted in the dry season, then more attention must be given to water needs. A newly installed plant needs its root ball kept moist until its roots have extended into the surrounding soil (about 2 weeks). After that, many plants need watering only when the soil in the root zone is getting dry. Watering should be deep, whether that be with drip, overhead, microemitter systems, or hand watering. (Natives actually prefer overhead, but if that’s your choice, do it sensibly, and that means do not overwater and do it before the sun comes up.) Once established, not all natives are low water users and drought tolerant. Some will need little to no water; others will need occasional deep watering; and some like regular moisture (e.g., riparian species).

A good sign that a plant is well established is when it doubles in size. Usually, you don’t see much growth during the first year or two,- that’s when the plant is spending most of its energy putting its roots deep in the ground. Once that is accomplished, more outward growth occurs.

Native species generally require little, if any pruning. Some species need to be cut back annually and any pruning beyond that is likely to be for aesthetic reasons or to remove diseased growth. The best time to prune is during the plant’s dormancy or right after flowering. Which brings up the fact that seasonal changes for many natives are the opposite of most non-natives. Winter rains stimulate growth which slows in the spring as flowers emerge. In the summer, dormancy begins as berries and fruits form. In the fall, berries and fruits have ripened, seeds are falling and most plants are fully dormant.

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Maintenance of your native wildlife garden- pest control

Ok….you have your new, wildlife friendly, native plant garden installed and you are happily watching it grow and suddenly your tranquility and pride are shaken by the presence of…..BUGS! Quel horror!!! Rather than panicking, that is the moment to remember what follows: a system called Integrated Pest Management or IPM. It is a system developed by growers who are, like you and me, concerned about the environment. In other words, an environmentally friendly approach to pest control.

The first question to ask and answer is: is there a problem? Insects are a normal part of a balanced eco-system, providing pollination service and, in some cases, insect control. Many of these good bugs are attracted to native plants. Examples are: ladybugs, lacewings, hover flies, mantids, parasitic wasps, spiders, bees, and dragonflies. Some damage from insects is therefore to be expected and it is only when damage becomes excessive do we need to become concerned.

As with human disease, the best treatment for plant disease is preventative treatment. For the home gardener, preventative measures include selecting plants that are healthy to begin with and planting them in locations that will meet their basic sunlight/soil/drainage needs, followed by proper watering, proper pruning (if needed), and proper feeding (if needed).

Assuming preventive measures are met, and excessive insect damage is occurring, the control measures that are least damaging to the environment are physical: a strong spray from a hose can dislodge harmful insects; damaged or diseased parts can be pruned; or a diseased plant can be totally removed. The next, least harmful measure is biological: one can purchase and introduce good bugs into the garden to control the bad bugs, though you are more likely to keep the good bugs around if you have plants in your garden that attract them (examples: sages, yarrow, buckwheat, ceanothus, lantana, rosemary, many herbs). The insect eating birds that are attracted to your garden will also keep the bad guys in check. Last are chemical controls. The least harmful of these is a soap solution. There are many other common household products that will not harm the environment that can be used to combat weeds, animal pests (such as snails, deer and rabbits), and fungal diseases as well as insects. The least desirable and most damaging to the environment are commercial, chemical pesticides (insecticides, herbicides, rodenticides). Got weeds? Pull ‘em, blow torch ‘em, spray ‘em with vinegar and use lots of mulch on bare soil. Got rats? Hang a barn owl nest box in your yard.

Learn more about non-toxic, environmentally-friendly, sustainable gardening practices at www.finegardening.com (click on pests and diseases).

Look after Mother Earth and she will nurture us and our wild friends….

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Why create a garden for wildlife?

In my youth, I considered myself lucky to live in an “advanced” civilization…in contrast to the “primitive” tribes in Africa or pre-colonial America. Now that I am much older and, I think, wiser, I have a different perspective on things. Our consumerist society has provided us with much comfort, ease and entertainment, but if one thinks long-term, it appears to be eroding our ability to sustain life on planet Earth. It was the tradition of Native Americans, when making decisions about tribal life, to ask what will be the effect seven generations from now? Nowadays, little thought is given to the effect of our decisions on the next generation, much less the next seven.

As our civilization “advances”, we continue to destroy much of the biodiversity upon which human life on Earth depends. We are, in fact, in the midst of the greatest extinction of plant and animal life since the dinosaur extinction 65 million years ago and it has been estimated that if it continues at this rate, we will lose HALF of our biodiversity by the end of this century. Poaching, pollution, invasive species, global warming, government sanctioned wildlife slaughter are all taking their toll on wildlife and wildlife habitat. Vast tracts of land are cleared of native flora and fauna to make way for yet more housing tracts, shopping malls, industrial parks, grazing fields and agriculture. Until recently, little thought was given to the effect of eliminating so much natural habitat on our future. Development is especially rapid in areas like coastal California which have a Mediterranean climate: hot, dry summers; cool, moist winters. There are only five small areas on Earth that share our climate and all have the potential of supporting a vast diversity of plant and animal life. Sadly, for every acre being preserved in these areas, eight acres are being lost.

We humans are the most invasive species on Earth. In the lower 48 states, although new-growth forests have increased in the last century, 95% of old-growth forests have been destroyed. This is approximately California’s loss as well. The Great Plains states at one time comprised one of the largest grassland areas in the world, providing habitat for a large variety of birds and other wildlife. Here in California, our Central Valley similarly had large swaths of grassland. 99% of these grasslands are now gone and the birds that depended on them are now the most threatened species in the country. Wetland losses, though reduced since the 1970’s and 80’s, are still immense: 91% of California’s wetlands are gone.

This is all very depressing to contemplate, but the good news is that there is growing awareness of how important restoration and preservation of natural habitat is. The Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, and many other groups are working hard to preserve our environment…our biodiversity. By creating a garden that is compatible with our climate and supports our native wildlife, each of us can contribute to this noble effort and to the health of our planet.

Alan Pollack, M.D.

Before retiring from the practice of psychiatry in 1995, Alan Pollack’s interest in woodworking led him to volunteer with Habitat For Humanity for several years. In 1997, he began as a volunteer with wildlife rescue/rehab groups. It was through them that he learned about the training given by the National Wildlife Federation and became a Wildlife Habitat Steward. Having been a life-long, home gardener and having a knack for landscape design, he was delighted to be able to wed two of his passions: the love of gardening and of wildlife. Since 2004, he has been giving free consultation and landscape designs to homeowners, churches, and schools,- anyone who wishes to create a garden that is attractive to wildlife as well as humans. He has served on the Board of the San Fernando Valley Audubon Society and leads their Audubon-at-Home Project. He has been giving his PowerPoint slide show/lecture (entitled “Restoring Habitat, One Yard at a Time”) to various groups who are interested in the goal of restoring and preserving wildlife habitat.